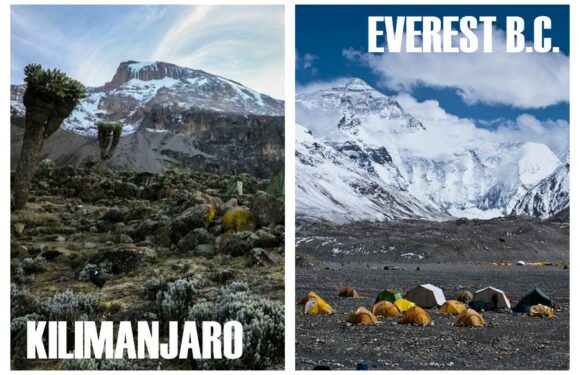

Mount Kilimanjaro, the highest peak in Africa, is famous due to its ice cap and glaciers. It’s a sight that might seem paradoxical given its location near the equator. However, this phenomenon can be explained through a combination of scientific, geographical, and climatic factors.

Snow on Kilimanjaro

First let’s discuss the presence of snow.

Snow on mountain tops in general is primarily a result of the interplay between altitude, temperature, and precipitation. Mountains can act as barriers to air flow, forcing any moist air masses to rise along the mountain slopes (a process known as orographic lift). As elevation increases, the temperature decreases. When moist air rises and cools, it condenses and turns into snow if the temperature is low enough. The end result is snow accumulation on mountain tops. Some mountains, especially those at very high altitudes, can maintain snow-covered peaks year-round.

Mount Kilimanjaro, at 19,341 feet (5,895 meters) tall, is one of these mountains that hosts a permanent snow cap at its summit. The high altitude and arctic zone conditions create an environment where snow can persist throughout the year.

Note that the volume of snow on the ground varies from season to season and from year to year. Kilimanjaro experiences wet and dry seasons. The long rainy season occurs from mid-March to early June, and the short rainy season occurs in the month of November. During the rainy periods, the mountain receives a substantial amount of precipitation, some of which is in the form of snowfall. Therefore, the chances of experiencing a full, snow covered peak are higher during the two rainy seasons.

During the dry seasons, the air is colder and drier. But, it snows far less and the clearer skies and intense solar radiation is typically too strong for the snow to stick. Therefore, snow does not accumulate as easily during these periods. Because most people climb Kilimanjaro during the dry season, it’s more likely than not that there will not be much snow when they summit.

But, the weather is unpredictable, so you never know what conditions you will experience regardless of when you visit. It’s possible you’ll see heavy snow or barely any snow at all.

Kilimanjaro’s Glaciers and Ice Cap

The glaciers on Kilimanjaro are remnants of an ice cap that once spanned a larger area of the mountain. These glaciers are believed to have formed approximately 11,700 years ago, at the end of the last Ice Age, a period known as the Pleistocene epoch. Snow, subjected to the mountain’s cold conditions, did not fully melt during warmer seasons. Over time, layers of snow compacted under their own weight, turning into ice.

This transformation from snow to ice involves a series of stages. Fresh snow first becomes firn, a denser form of snow that is intermediate between snow and glacier ice. Continued compaction and recrystallization of firn eventually lead to the formation of solid ice, establishing the glaciers seen on Kilimanjaro.

The formation and maintenance of these glaciers are highly dependent on the balance between accumulation (mainly through snowfall) and ablation (the melting and sublimation of ice). Kilimanjaro’s unique geographical position near the equator means that it receives solar radiation throughout the year, which would typically discourage glacier formation. However, the high altitude of the summit ensures temperatures remain low enough for snow to persist and gradually turn into ice.

While these natural processes that have sustained Kilimanjaro’s ice cap for millennia, the glaciers have been noticeably retreating over the past century. Scientific studies attribute this shrinkage primarily to global climate change, which has led to higher overall temperatures and altered precipitation patterns. The reduction in cloud cover during the dry seasons, coupled with decreased snowfall during the wet seasons, has exacerbated the ice loss.

In conclusion, the presence of snow, glaciers, and an ice cap on Mount Kilimanjaro is a result of its high elevation, geographical position, and specific weather patterns. However, the observable decline in glacier size highlights the urgent need for global environmental stewardship to preserve these natural wonders.