Mount Kilimanjaro’s numerous climate zones, also called vegetation zones and ecological zones, are a direct result of its great height and geographical location. The mountain rises from the plains of East Africa to an exteme altitude of 19,341 feet (5,895 meters), which creates a series of climates and habitats stacked on top of each other.

Mount Kilimanjaro’s diverse zones stem from a combination of many factors.

- Pressure and Temperature Changes: As altitude increases, air pressure decreases, leading to significant changes in temperature. Each zone on Kilimanjaro exists because of a specific range of temperature and precipitation that supports different types of life.

- Microclimates: Kilimanjaro is a standalone massif, which means it creates its own isolated climates. The mountain’s slope influences the amount of sunlight received, wind exposure, and drainage, contributing to the microclimates.

- Proximity to the Equator: Kilimanjaro is near the equator, which allows tropical conditions at its base. The equatorial sun coupled with the mountain’s height spans the climatic conditions from the equatorial to the arctic at the summit.

- Rain Shadow Effect: The mountain intercepts the moist air coming from the Indian Ocean, creating a rain shadow on the leeward side. This results in variations in rainfall and humidity, which in turn affects the type of vegetation and ecosystems in each zone.

- Volcanic Soil: The rich volcanic soil at the lower levels of Kilimanjaro supports lush vegetation and agriculture, which transitions into different types of soil that support less diverse plant life as the altitude increases.

- Agriculture and Settlements: The lower zones have been influenced by human activity, such as agriculture, which has modified the original ecological settings.

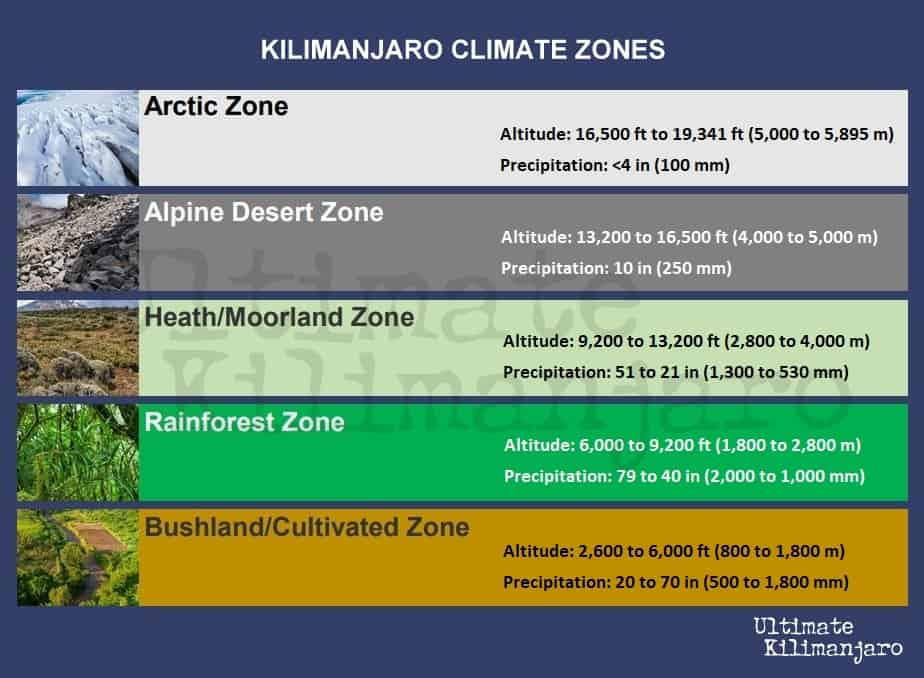

Below are Mount Kilimanjaro’s climate zones from the lowest to the highest altitude along with the average annual precipitation and zone characteristics.

Bushland/Cultivated Zone

Altitude: 2,600 to 6,000 ft (800 to 1,800 m)

Precipitation: 20 to 70 in (500 to 1,800 mm)

The lowest elevation climate zone is the bushland/cultivated zone, resting a half mile or more above sea level. Farmland, grasslands and populated human settlements characterize this zone. The town of Moshi is located here.

Natural bush, plains, and lowland forests once covered the region. However, because this area is rich with fertile volcanic soil, it makes an ideal land for agriculture. The Chagga people settled on these lower slopes to farm a variety of crops, such as highly prized coffee and tropical fruits. The grounds are irrigated by underground channels tunneling through the earth from the lush rainforest nestled above.

Many of the local mountain guides hail from the nearby villages. Large wild animals are rarely seen here, having been eliminated by farmers generations ago. However, small nocturnal mammals such as galagos and tree hyrax still thrive. Birds, such as speckled mousebirds and tropical boubou, are also plentiful.

Rainforest Zone

Altitude: 6,000 to 9,200 ft (1,800 to 2,800 m)

Precipitation: 79 to 40 in (2,000 to 1,000 mm)

The rainforest is drenched by six to seven feet of rain per year and bursts with biodiversity. During the day, warm temperatures and high humidity characterize this densely forested climate zone. However, rainy nights can produce surprisingly low temperatures. Climbers definitely want to have their rain gear handy to protect themselves from the constant drizzle.

The rainforest presents the most abundant opportunities for viewing unique types of African flora and fauna. Various species of orchids, ferns, sycamore figs, olive trees, and palms dripping with hanging mosses are found here. Camphorwood trees reach as high as 130 feet through the canopy grasping for sunlight. Blue and Colobus monkeys gallivant through the trees, loudly beckoning mates, and a vibrant cacophony of sounds emanate from the diverse population of birdlife.

Climbers approaching the summit from the Rongai, Lemosho, Shira or Northern Circuit routes may be lucky enough to spot elephant, buffalo, antelope and an occasional predator drifting through in search of a wayward meal.

Heath/Moorland Zone

Altitude: 9,200 to 13,200 ft (2,800 to 4,000 m)

Precipitation: 51 to 21 in (1,300 to 530 mm)

The heath/moorland zone is a semi-alpine zone is characterized by heath-like vegetation and abundant wild flowers. According to mountain medicine, the heath zone is in the “high altitude” region. The first symptoms of acute mountain sickness may begin to appear in some climbers.

Most routes enter this zone on the second day of hiking, and depending on the route duration, may spend several days at this altitude. This is recommended as it allows climbers to gradually acclimatize to the decreasing oxygen and the higher elevations to come.

As we move higher, the humidity and dense forest surroundings begin to give way to drier air and cooler temperatures. The flora thins into smaller shrubs like heather, and the presence of fauna becomes increasingly scarce. The most prominent flora are the unique and iconic Senecios (also known as groundsels) and Giant Lobelias. Kilimanjaro’s giant Senecios and Lobelia are endemic to the region. The Senecios, which translates from Latin to “old man,” have thick weathered stems topped with large, succulent rosettes. Lobelias resemble oddly-shaped palm trees with rosettes that close in the evenings to guard against the chilly night temperatures.

The most common birds seen in the heath zone are the easily recognizable black and white crows which forage around camp. Sometimes, large birds of prey such as the crowned eagle and lammergeyer soar overhead.

Current weather conditions for Mount Kilimanjaro’s heath zone can be found here.

Alpine Desert Zone

Altitude: 13,200 to 16,500 ft (4,000 to 5,000 m)

Precipitation: 10 in (250 mm)

The alpine desert is comprised of volcanic rocks of all shapes and sizes. This zone receives little water and correspondingly light vegetation exists here. The temperature can be quite hot during the day. The thin air and proximity to the equator result in very high levels of solar radiation. Applying liberal amounts of sunscreen is an absolute must. During the night, temperatures often plummet to well below freezing, leaving a dusting of morning frost on the tents.

This zone is in the “very high altitude” region of mountain medicine. For ideal acclimatization, climbers should spend considerable time here. Our preferred routes will venture into this zone on a few occasions, before sleeping here at high camp on the night before the summit. We encourage clients to “climb high, sleep low” which will reduce the ill effects of altitude.

This arid zone has thin soil that retains little water, making it inhospitable to most plant and animal species. Everlastings are one of the main plant species that can withstand such harsh conditions, as well as tussock grasses and varieties of moss. A few of the animals that make appearances in the moorland will wander to these elevations, but the occurrences are very rare.

Current weather conditions for Mount Kilimanjaro’s alpine desert zone can be found here.

Arctic Zone

Altitude: 16,500+ ft (5,000+ m)

Precipitation: <4 in (100 mm)

The final region of the climb up Kilimanjaro is the arctic zone.

Finding a region like this in Africa’s equatorial belt is like finding a swath of rainforest in the middle of an Arctic glacier. Characterized by ice and rock, there is virtually no plant or animal life at this altitude. Glacial silt covers the slopes that were once concealed by the now receding glaciers visible from Kilimanjaro’s crater rim. Nights are extremely cold and windy, and the day’s unbuffered sun is powerful.

Mountain medicine classifies this zone as “extreme altitude.” Oxygen levels are roughly half of what they are at sea level, making breathing slow and labored.

Climbers will enter this zone on the way to the summit. Because this is typically done in the middle of the night, expect to wear several layers of clothing on the top and bottom. You’re going to have to endure very cold or freezing temperatures and strong winds for 6-8 hours.

With the exception of crater camp routes, we don’t sleep in this zone. It’s likely that climbers will experience varying degrees of altitude related symptoms at these elevations. Therefore, we try to avoid spending too much time here. We summit and descend quickly before AMS can escalate.