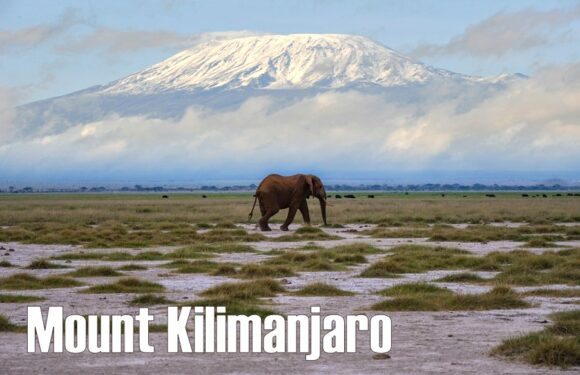

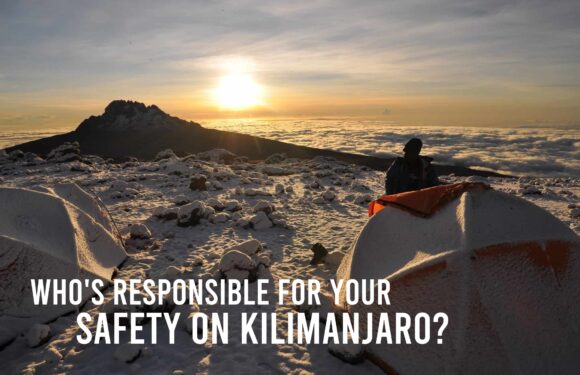

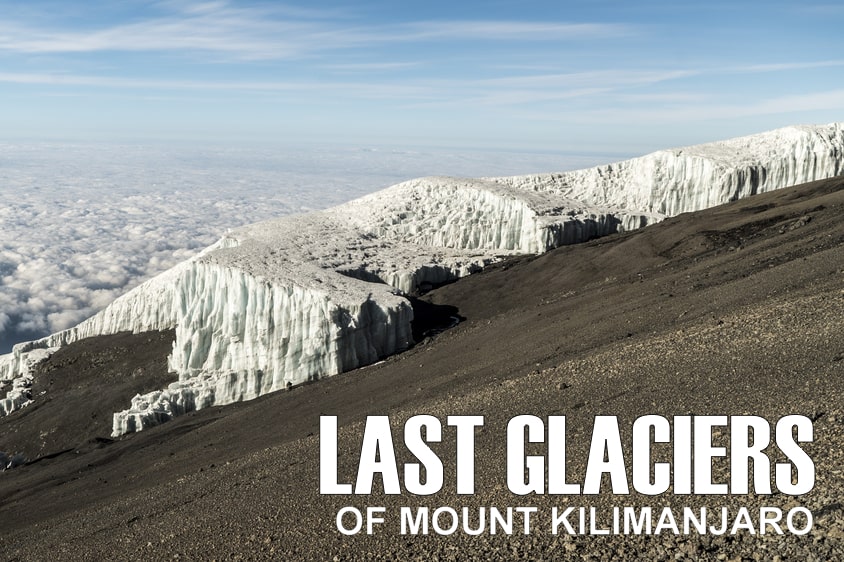

Mount Kilimanjaro is renowned for its ice capped peaks.

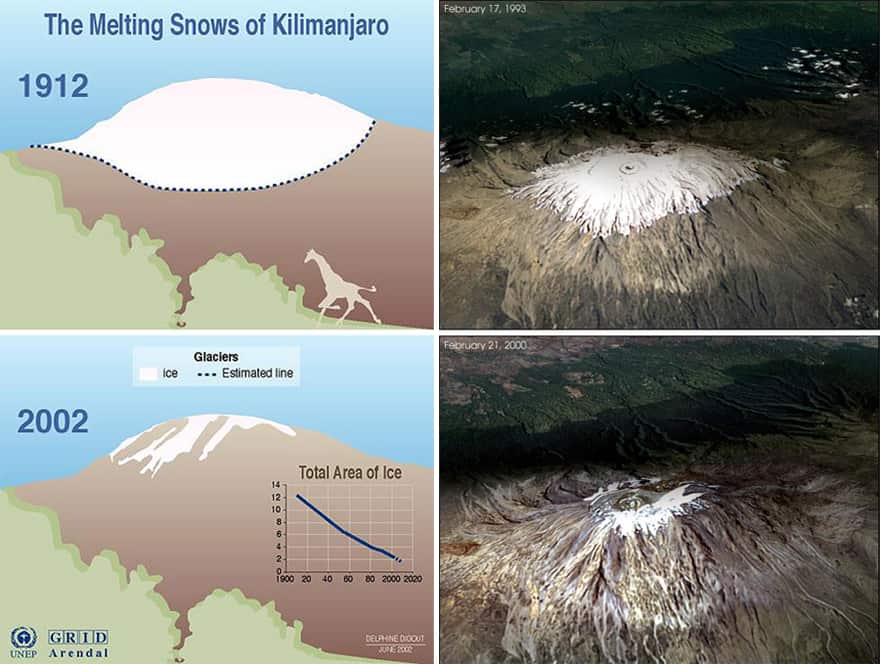

Once upon a time, huge glaciers adorned the slopes of Kilimanjaro. But due to the relentless march of climate change, they now exist as fragile remnants, dwindling year by year. In 1880, Kilimanjaro’s glaciers covered an area of 20 square kilometers and extended from the summit down to 17,000 feet (5,200 meters). In 2016, the glaciers are estimated to cover an area of just 1.7 square kilometers and extend down to 19,000 feet (5,800 meters), or just a few hundred feet below the summit.

In this article, we will discuss the history and current status of the last remaining glaciers of Mount Kilimanjaro.

Kilimanjaro’s Glacial History

When Kilimanjaro was first observed by European explorers in the 19th century, the summit was heavily glaciated. Historical accounts and photographs from the late 1800s depict a mountain capped with extensive ice. Mount Kilimanjaro is believed to have harbored glaciers for more than 11,000 years.

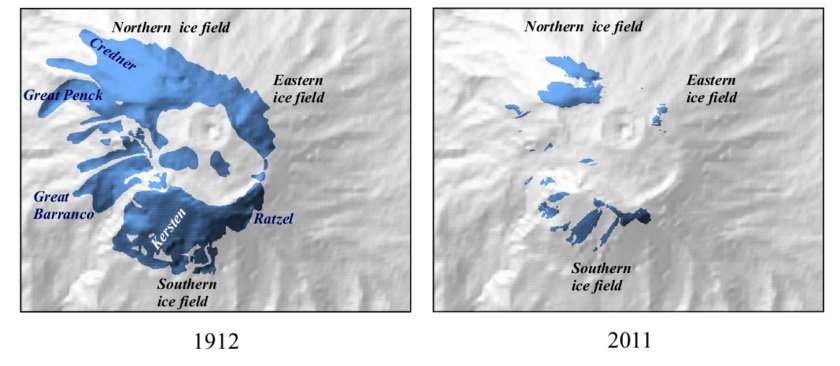

During the last century, these icy giants have faced a dramatic decline, primarily due to global warming. The once extensive glaciers have been reduced to isolated patches, many of which have vanished altogether. This transformation underscores the urgency of addressing climate change and its consequences on our planet’s fragile ecosystems.

How Do Glaciers Form?

Glacier formation starts with snowfall in regions where snow does not fully melt away, such as high mountainous areas or polar regions. Here, the snow begins to accumulate, layer upon layer. Over time, the weight of the new snow compresses the older snow beneath it. This compression leads to the recrystallization of snow into a substance called firn.

As more snow piles up and further compaction occurs, this firn gradually transforms into solid glacial ice. This transformation is neither quick nor abrupt. It’s a slow process that can span decades or centuries, depending on environmental conditions and the rate of snowfall. Once formed, glaciers are constantly on the move, though this movement is slow. They flow under their own weight and the pull of gravity, reshaping the landscape as they travel.

What is an Ice Field?

An ice field is a vast, flat expanse of interconnected glaciers. It differs from an ice cap, which typically has a central dome-like shape. Ice fields are generally flat and spread out over large areas. They serve as the feeding grounds for smaller glaciers, providing the source from which these glaciers flow outward.

The thickness of an ice field can vary significantly. For instance, the Antarctic ice sheet is about 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) thick. This thickness is a function of the accumulation of snow and ice over extensive periods. Unlike glaciers, which are defined by their flow, ice fields are characterized more by their expanse and the role they play in feeding other glaciers.

Kilimanjaro’s icefields – the Northern Icefield, Southern Icefield and Eastern Icefield – were once interconnected and formed part of a continuous body of glacial ice on Mount Kilimanjaro when first scientifically examined in 1912.

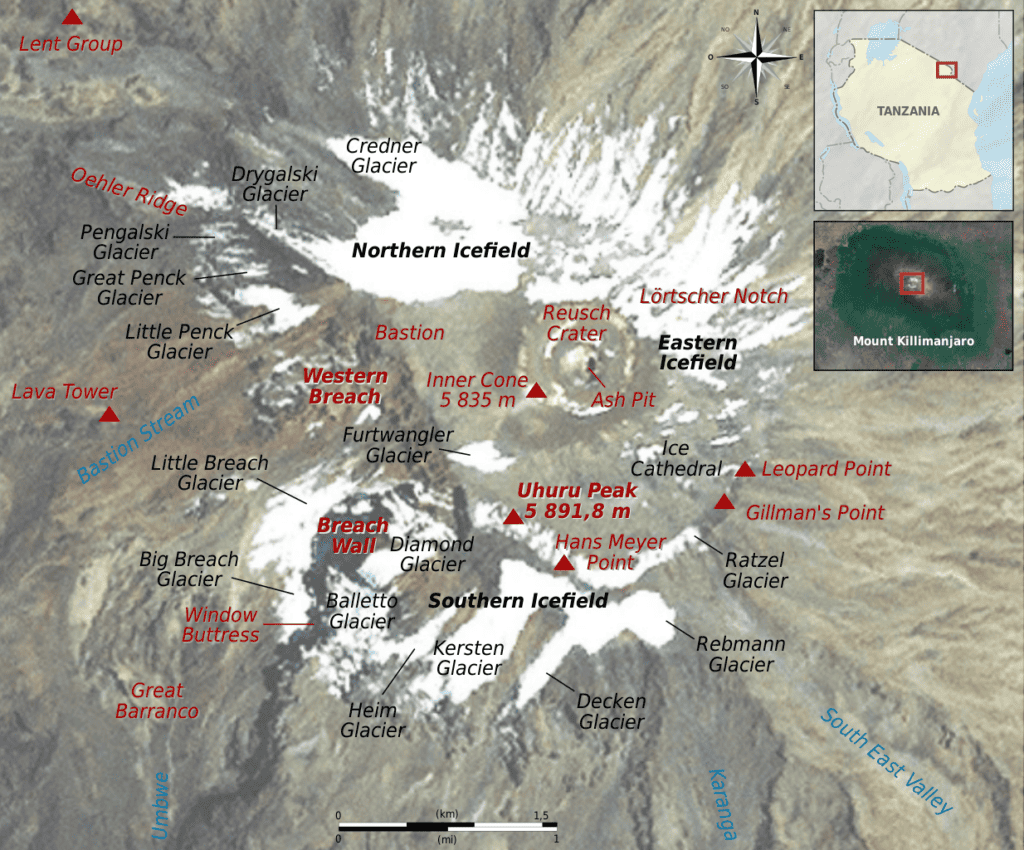

The Northern Icefield

On Kilimanjaro’s northern face, the Northern Icefield used to hold a cluster of immense glaciers, including Credner Glacier, Dryglaski Glacier, and the Penck Glaciers. These glaciers formed over millennia as snow gradually turned into ice under pressure.

- Credner Glacier: Subject of extensive scientific study. Retreat monitored to understand climate change impacts on high-altitude glaciers.

- Drygalski Glacier: Located on Kilimanjaro’s northwest slope, much of this once massive glacier no longer exists today.

- Penglaski Glacier (Vanished): Previously located on the western slope of Mount Kilimanjaro. Has disappeared from Kilimanjaro.

- Great Penck Glacier (Vanished): Previously located on the western slope of Mount Kilimanjaro. Separated from the Northern Ice Field between 1962 and 1975. No longer present on Mount Kilimanjaro.

- Little Penck Glacier (Vanished): Was adjacent to the Great Penck Glacier. Faced a similar fate to the Great Penck Glacier and has disappeared.

The Southern Icefield

The Southern Icefield, situated on the southern slopes of Kilimanjaro, was an expansive region of interconnected glaciers. It played a pivotal role in Kilimanjaro’s glacial history and is important for sustaining the mountain’s surrounding ecosystems. The formation of the Southern Icefield resulted from centuries of snow accumulation ultimately giving rise to these glaciers.

The Southern Icefield encompasses various glaciers, including the Furtwangler Glacier, Barranco Glacier, Arrow Glacier, Little Breach Glacier, Ballette Glacier, Diamond Glacier, Kersten Glacier, Decken Glacier, Rebmann Glacier, and Ratzel Glacier.

Nonetheless, like its counterparts, the Southern Icefield faces the dire consequences of climate change. The receding glaciers within this icefield have prompted concerns about the long-term availability of freshwater resources and their potential impact on local ecosystems.

- Furtwangler Glacier: Located near the summit of Kilimanjaro, the most well-known glacier on the mountain. It has witnessed substantial retreat over the years. Named after German geographer Walter Furtwängler who climbed Kilimanjaro in 1912.

- Barranco Glacier: Previously known as the Great Barranco Glacier, lies on the southwestern slopes of Kilimanjaro. It has lost much of its former grandeur, leaving behind only two disconnected and dormant ice bodies.

- Arrow Glacier (Vanished): Once known as the Little Barranco Glacier, was a small but notable remnant on the mountain’s southern slopes. Located above Arrow Glacier camp, a site used for the Western Breach approach to the summit. The glacier was named for its distinctive arrowhead shape. It has now vanished.

- Uhlig Glacier (Vanished): Previously located on the northwest part of the Western Breach. Named after Carl Ludwig Gustav Uhlig, a German geographer and meteorologist. It is now gone.

- Little Breach Glacier: Was located next to Arrow Glacier, on the wall of the Western Breach.

- Balletto Glacier: Named after Italian glaciologist Giuseppe Balletto. Found on the southern slope of Mount Kilimanjaro, it is one of the few remaining ice masses on the mountain.

- Diamond Glacier: Located adjacent to Balletto Glacier, part of the Southern Icefield.

- Heim Glacier: Situated in the southern ice fields, known for glacier climbing.

- Kersten Glacier: Named after Reinhard Maack’s student, located on Kilimanjaro’s southern slopes.

- Decken Glacier: Named in honor of explorer Baron Carl Claus von der Decken, situated on the mountain’s southern slopes.

- Rebmann Glacier: Named after German missionary Johann Rebmann, who first reported the existence of glaciers on Kilimanjaro. It was once part of an enormous ice cap.

- Ratzel Glacier: Located on the southeastern side of Kilimanjaro, another glacier affected by climate change.

The Eastern Icefield

The Eastern Icefield is a less-recognized segment of Mount Kilimanjaro’s ice cap. As a result, many of its glaciers are unnamed.

The Disappearance of Glaciers on Kilimanjaro

Sadly, several glaciers on Mount Kilimanjaro have vanished completely or have reduced to such small remnants that they are no longer recognizable. The dramatic decline of glaciers on Mount Kilimanjaro is a sign of the profound impact of climate change. Rising global temperatures have led to increased ice melt, reduced snowfall, and altered precipitation patterns in the region. These factors, combined with other environmental changes, have accelerated the retreat of Kilimanjaro’s glaciers.

Scientists and researchers have been conducting extensive studies to understand the mechanisms driving this glacial loss. The retreat of glaciers on Kilimanjaro is not only an ecological concern but also has significant implications for the local communities that rely on the mountain’s water resources for agriculture and drinking water.