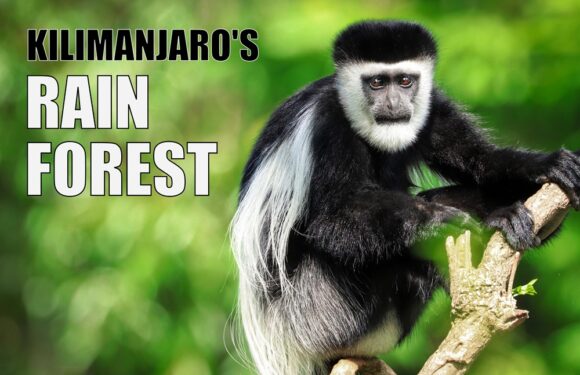

When traveling to Africa, most people start getting excited about seeing animals like lions, rhinos, elephants, giraffes, buffalo, leopards, and more. All of these animals live in the lower reaches of Kilimanjaro, but most of the sightings are rare.

But what about the animals that you didn’t even consider spotting? There are lots of unique animals that you could potentially see on your climb, and although sightings are infrequent, we still encourage you to keep your eye out for a rustle in the bushes, or a flash of movement on the slopes. Here are six of the lesser-known, fascinating animals that you might spy on your journey to the top of the African continent.

Civet

Lithe bodied, agile, and mostly nocturnal, the African Civet is a solitary animal with unique coloration. They prefer living in river and woodland areas where they spend most of the day sleeping amongst dense vegetation. Black and white stripes and blotches cover its coarse fur creating a pattern that effectively camouflages this medium-sized mammal of the Viverridae family. The black bands surrounding its small eyes and tiny ears can often trick onlookers into thinking this may be a raccoon at first glance. Civets have a disproportionally large rump in comparison to the rest of their body, and the spikey pelage on their dorsal crest that raises when threatened. They have a short, broad neck, a long bushy tail, and a pointed muzzle.

Civets are generally omnivorous, imbibing vegetable matter along with a variety of small animals, invertebrates, amphibians, eggs, and carrion. Sometimes, civets prey on venomous snakes. Their keen sense of smell and sound helps them detect food sources rather than depending on their eyesight. Fluid produced by the Civets perineal glands and used for marking territory (aptly named civet), has been harvested for hundreds of years and utilized in the perfume industry. Since the creation of synthetic musk, however, usage of civet has decreased. To learn more about the use of Civet in perfume, check out this article on 5 Icky Animal Odors That Are Prized By Perfumers.

Female civets can have up to 3 litters of 1-4 young per year. Young are born able to crawl, which is advanced amongst carnivores, and they can leave their nest two and a half weeks after birth.

Crested Porcupine

Covered almost entirely in dark brown and black bristles, the crested porcupines claim to fame is its defensive quills. Sturdier quills marked with alternating light and dark bands run along its head, name, and back that is raised into a crest to guard against predators. These quills are about 14 inches in length (35 cm), and can quickly detach and lodge themselves into unlucky hunters. At the end of the porcupines short tail, there are rattle-quills which produce a hissing sound when vibrated in warning. When threatened, they fan and whirr their quills, stamp their feet, and finally charge, stabbing the enemy with their thicker, short barbs.

Porcupines have been known to take down lions, leopards, and hyenas in this fashion. There are even reports that porcupines have attacked and killed humans so be sure to keep your distance.

Herbivorous, the crested porcupine imbibes a variety of roots, bulbs, leaves, insects small vertebrates and the occasional bit of carrion. They are a terrestrial rodent and found in Italy, North Africa, and Sub-Saharan Africa. Porcupines swim, but rarely climb trees. They are nocturnal and have a penchant for collecting hundreds of bones that they hide in underground chambers, which they gnaw on for calcium.

Crested porcupines are monogamous, and breed throughout the year. Females produce litters of one or two individuals weighing just over 2 lbs after two months of gestation. After a week, the younglings spines begin to harden, and they can leave the den. Sexual maturity approaches at around one to two years when they have reached their adult weight, ranging from 29-60 pounds (13-27 kg).

Serval

Medium-sized, and slender, the Serval is a wildcat that tends to be solitary and actively hunts during the day as well as night. Servals sport a golden-yellow coat with a combination of stripes and spots and a short, black-tipped tail. Their heads are small, and their ears are large, and they have the longest legs of any cat relative to their body size often standing 21-24 inches (54-62 cm) at the shoulder, and weighing anywhere from 20-40 lbs (9-18 kg).

Rodents are the serval’s primary prey, but they also hunt birds, frogs, insects, and reptiles. Like many smaller cat species, they also feed on grass to facilitate digestion or act as an emetic to clear away fur balls accumulated in their digestive system from grooming. Occasionally, they take on larger prey such as duikers, hares, flamingo, and small antelope but most of their prey weighs under 7 ounces (200 g). A study conducted in Ngorongoro crater determined that servals were remarkably efficient hunters, employing their acute hearing as they stalk through high savannah grasses or wetland reeds and pounce or leap on their prey with a success rate of 62% averaging 15-16 kills in a 24 hour period.

Both sexes reach sexual maturity as early as 1-2 years old. Females give birth to a litter of 1-4 kittens after a two-three month gestation period. Kittens are blind at birth and open their eyes after about 1 and a half to two weeks. After a month, the mother starts weaning the kittens that will begin to hunt on their own after they are about six months old.

Abbott’s Duiker

A duiker is one of the most widespread of all forest antelopes. This particular species is named after Dr. W.L. Abbott, who collected a specimen on Kilimanjaro between 1888 and 1889. The word ‘duiker’ means to dive, referring to the animal’s movements to escape a threat. It stands about 26 inches (65 cm) tall and weighs around 120 lbs (55 kg).

Abbott’s duiker roams in the highlands of north-eastern and central Tanzania including the foothills of Mount Kilimanjaro. Very little is known about its behavior in wild due to its secretive nature and its habitat. It is believed that the Abbott duiker is mostly nocturnal, likely spending the day resting in dense vegetation. It has been filmed only with camera traps.

The species has a dark brown coat which is lighter underbelly. Only male duikers have horns, which measure a few inches long. It feeds on plant matter in forest clearings, but they also eat fruit, pods and seeds, roots, bark, flowers, fungi, insects and even small birds and reptiles.

Genet

Slender, spotted genets are small and agile, with cat-like reflexes and superb climbing skills. They are the only animal in the viverrid family able to stand on its hind legs. Primarily, they make their homes on the ground, but they also spend a fair amount of time nimbly moving amongst the trees. Most genets have spotted fur with a long ringed tail, but a few all black (melanistic) individuals exist as well. Their bodies nearly the same length as their tails and they have large ears, eyes, and a pointed muzzle.

Genets are omnivorous, feeding primarily on plant matter, fruit, invertebrates, small vertebrates, fish, and various types of insects. They are opportunistic animals and have even been spotted riding atop rhinoceros and buffalo.

Solitary by nature, genets usually only come together during mating season. Female rear litters of up to five young one to two times per year and raise the offspring by themselves.

Tree-hyrax

Tree-hyraxes, also known as tree dassies, are small nocturnal mammals distantly related to elephants and sea cows. Fur in their soft, dense coats ranges from pale grey to dark brown depending on the region to aid with camouflage. Their rubbery soled front feet have four toes, while their back feet have three to help them climb.

Tree hyraxes, unsurprisingly, spend a lot of time in trees. It is a nocturnal forager. It is mainly herbivorous, feeding on leaves, fruits, bark, twigs, and grasses as well as an occasional insect. The tree-hyrax in not endangered, but it is rare to spot one. They are incredibly shy.

The male Tree Hyrax has a distinctive call that begins with loud measured cracking sounds followed by a series of ‘unearthly screams’ and concluded with a series of shrieks which makes them more often heard, than seen. Many people will often mistake the cries for a catfight. Females also call, but they do not have the vocal power of their mates. Calling times tend to be most frequent a few hours after dark and after midnight.

Aardvark

Sometimes known as the “African Ant Bear,” the aardvark is the sole living species of the mammalian order Tubulidentata. Now living solely in the southern two-thirds of Africa, aardvark fossils have been found in Europe and the Near East dating back as far as 5 million years ago. The etymology of the word aardvark comes from the Afrikaans word erdvark, meaning “earth” or “ground pig.” The order name, Tubulidentata, is a result of the animals tubule-style teeth. People often assume it is related to pigs or anteaters, but it’s closest living relatives are elephant shrews, tenrecs, golden moles, hyraxes, elephants, and sirenians.

An insectivore, it has a long, pig-like snout which it uses to sniff out ants and termites during the night. Powerful legs armed with sharp toed claws allow it to dig the insects out of their hills or create burrows to house and rear their young. It avoids areas that are mostly rocky for their lack of ample food and burrow sources. At night, when departing their burrows, aardvarks will pause at the entrance for about 10 minutes sniffing and listening with perked ears before it begins foraging. Their holes can be large enough for a person to enter, and play an important role in African ecosystems, later providing homes or refuges for other animals.

Aardvarks are solitary, meeting as pairs only to mate. After seven months of gestation, one wrinkled floppy-eared cub will be born weighing 3.7-4.2 pounds (1.7-1.9 kg). Cubs can accompany their mother out of the burrow after two weeks, but don’t start eating termites until nine weeks. Mothers wean younglings at three-four months. Cubs remain with their mothers until the next yearly mating season and reach sexual maturity around the age of two.

Sub-Saharan Africa and the region surrounding Mount Kilimanjaro in Kenya and Tanzania provides some of the most phenomenal wildlife viewing opportunities in the world. These animals may not be as famous as some of the other exotic animals Africa has to offer, but they are just as unique and exciting. We encourage you to keep a look out for them on your climb to Kilimanjaro.

__________