Volcanoes are openings in Earth’s crust where magma reaches the surface. Over time, repeated eruptions can build enormous landforms that dominate entire regions. Some volcanoes rise steeply. Others spread across vast distances.

While elevation measures how high a summit reaches above sea level, it says nothing about how much volcanic material exists or how much land a volcano covers. The correct geological metrics for size are total volume and surface footprint. These reflect how much magma has been erupted and how widely it has spread.

Below are the fifteen largest volcanoes in the world, ranked by overall size, not elevation.

The 15 Largest Volcanoes in the World (by Size)

| Rank | Volcano | Location | Approximate Area | Status | Typical Climb Style |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mauna Loa | USA | 5,271 sq mi (13,500 sq km) | Active | Long day hike or overnight backpack |

| 2 | Tamu Massif | Pacific Ocean | 120,000 sq mi (311,000 sq km) | Extinct | Not climbable |

| 3 | Mauna Kea | USA | 5,200 sq mi (13,470 sq km) | Dormant | Long day hike |

| 4 | Mount Kilimanjaro | Tanzania | 1,460 sq mi (3,780 sq km) | Dormant | Multi-day trek |

| 5 | Pico de Orizaba | Mexico | 1,250 sq mi (3,240 sq km) | Dormant | One to two-day climb |

| 6 | Mount Elbrus | Russia | 1,200 sq mi (3,110 sq km) | Dormant | Multi-day climb |

| 7 | Mount Damavand | Iran | 1,000 sq mi (2,590 sq km) | Dormant | Two to three-day trek |

| 8 | Mount Etna | Italy | 460 sq mi (1,190 sq km) | Active | Long day hike |

| 9 | Mount Shasta | USA | 460 sq mi (1,190 sq km) | Dormant | Two-day climb |

| 10 | Mount Rainier | USA | 390 sq mi (1,010 sq km) | Active | Multi-day climb |

| 11 | Mount Sidley | Antarctica | 250 sq mi (650 sq km) | Dormant | Expedition |

| 12 | Mount Fuji | Japan | 480 sq mi (1,240 sq km) | Dormant | Long day hike |

| 13 | Mount Teide | Spain | 720 sq mi (1,860 sq km) | Dormant | One to two-day hike |

| 14 | Sangay | Ecuador | 300 sq mi (780 sq km) | Active | Expedition |

| 15 | Cotopaxi | Ecuador | 300 sq mi (780 sq km) | Active | Two-day climb |

1. Mauna Loa

Mauna Loa is the largest volcano on Earth by total volume and footprint. It covers roughly 5,271 square miles (13,500 square kilometers), nearly 5% of the island of Hawaii. Its immense size is the result of its shield volcano structure. Low-viscosity basaltic lava flows easily and travels long distances before cooling, allowing the volcano to grow outward rather than upward over hundreds of thousands of years.

Mauna Loa formed over the Hawaiian hotspot and is classified as active, with its most recent eruption occurring in 2022. Although its summit rises only 13,681 feet (4,170 meters) above sea level, the volcano’s base begins far below the ocean floor. When measured from base to summit, its 33,500 feet (10,210 meters) tall.

From a climbing perspective, Mauna Loa is non-technical but physically demanding. Ascents are typically long day hikes or overnight backpacking trips, depending on route choice and starting elevation. The mountain’s enormous footprint creates sustained mileage, gradual elevation gain, and long summit days with little natural shelter. Terrain consists largely of lava rock, which can be uneven, abrasive, and slow to travel.

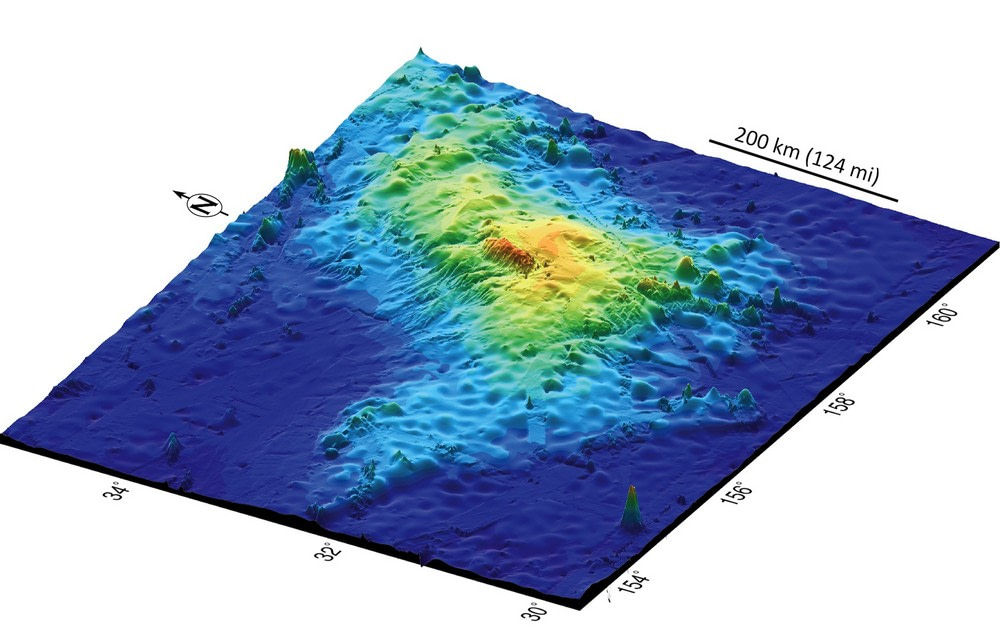

2. Tamu Massif

Tamu Massif is the largest single volcano ever discovered. It lies entirely beneath the Pacific Ocean and covers an estimated 120,000 square miles (311,000 square kilometers), making it larger than many countries by surface area alone.

Tamu Massif formed through massive fissure eruptions that released enormous volumes of low-viscosity lava. These flows spread outward in thin sheets rather than building a steep cone. The volcano is now considered extinct, with no evidence of ongoing magmatic activity. Its discovery reshaped scientific understanding of how large volcanic systems can become.

Tamu Massif is not a climbing objective. Its importance is geological rather than practical. Its inclusion highlights why elevation is a poor proxy for size and why many of Earth’s largest volcanoes remain hidden beneath the ocean.

3. Mauna Kea

Mauna Kea rivals Mauna Loa in total mass and footprint. It formed over the same Hawaiian hotspot and shares a similar shield volcano structure. While slightly smaller in surface area, Mauna Kea is steeper and denser, giving it immense overall volume.

Mauna Kea is classified as dormant. From base to summit, it measures approximately 33,511 feet (10,210 meters), making it taller than Mount Everest when measured this way. Everest remains the highest mountain above sea level at 29,032 feet (8,849 meters). Most of Mauna Kea’s height lies beneath the ocean surface, which is why it appears modest compared to continental peaks.

The summit of Mauna Kea hosts some of the world’s most advanced astronomical observatories, positioned here due to the mountain’s altitude, dry air, and stable atmospheric conditions.

Climbing Mauna Kea is non-technical but serious. Ascents are often done as long day hikes from high trailheads. Altitude, cold temperatures, and weather exposure are the main challenges. The volcano’s size is experienced through sustained elevation gain and distance rather than steep or technical terrain.

4. Mount Kilimanjaro

Mount Kilimanjaro is the largest volcano in Africa by volume and footprint. It consists of three volcanic cones, Kibo, Mawenzi, and Shira. The broad Shira Plateau, an eroded volcanic structure, contributes significantly to Kilimanjaro’s overall mass.

Kilimanjaro formed through prolonged volcanic activity rather than a single cone-building phase. It is classified as dormant. The last known eruption occurred roughly 150,000–200,000 years ago. Its size reflects repeated lava flows, collapses, and structural evolution over long geological time.

From a climbing perspective, Kilimanjaro is a multi-day trek rather than a technical climb. Most routes take five to nine days. Its size is felt through long daily distances, cumulative elevation gain, and altitude stress rather than steepness or exposure.

5. Pico de Orizaba

Pico de Orizaba is the largest volcano in North America by total volume. It rises from a high plateau in central Mexico, giving it a massive overall structure despite a more compact footprint than large shield volcanoes.

Pico de Orizaba is classified as dormant. Its size comes from long-lived eruptive cycles that built thick layers of lava and pyroclastic material over time. Seasonal glacial ice near the summit adds to its imposing appearance but does not define its geological mass.

Climbers typically ascend Pico de Orizaba in one or two days. Routes are generally non-technical, though snow and ice travel are often required near the summit. The volcano’s size is felt through a long summit day, significant elevation gain, and the effects of altitude.

6. Mount Elbrus

Mount Elbrus is the largest volcano in Europe by total volume and footprint. It dominates the western Caucasus and rises from a broad base built by overlapping lava flows and volcanic deposits. Although erosion has softened its profile, the mountain retains enormous mass spread across a wide area.

Elbrus is classified as dormant. Its volcanic activity ceased long ago, but its structure reflects multiple eruptive phases that added layer upon layer of material. The twin summits are remnants of this complex growth rather than separate peaks.

From a climbing perspective, Elbrus is a multi-day ascent. Routes are generally non-technical by mountaineering standards, but glaciers, altitude, and rapidly changing weather increase difficulty. The volcano’s size translates into long summit pushes, even when using high camps or lifts. Climbers often underestimate the physical demand created by its broad slopes and sustained elevation gain.

7. Mount Damavand

Mount Damavand is the largest volcano in the Middle East by total volume and footprint. It rises prominently from the Alborz range and sits on an already elevated plateau, which significantly increases its overall mass relative to surrounding terrain. Damavand’s size comes from repeated lava flows and explosive eruptions that built a wide, symmetrical cone over long geological time.

Mount Damavand is classified as dormant, though active fumaroles near the summit indicate lingering geothermal heat. Its volcanic structure is relatively intact, with limited erosion compared to older systems, allowing it to retain much of its original mass.

From a climbing perspective, Damavand is typically ascended over two to three days. Routes are non-technical, but the volcano’s size creates long approaches and sustained elevation gain from high starting points. Loose volcanic scree is common on the upper slopes, slowing progress and increasing fatigue. Altitude, wind, and sulfur gases near the summit further compound the physical demands. Climbers experience Damavand as a test of endurance driven by scale rather than steepness or technical difficulty.

8. Mount Etna

Mount Etna is one of the largest volcanoes in Europe by footprint and one of the most active volcanoes in the world. It dominates eastern Sicily and has grown laterally through thousands of years of frequent eruptions. While its summit height fluctuates due to collapses and lava accumulation, its true size lies in the vast area covered by lava flows and volcanic deposits.

Mount Etna is classified as active. Its structure is constantly evolving, with new vents opening and older ones collapsing. This continuous rebuilding contributes to its large footprint even as its profile changes.

From a climbing standpoint, Etna is usually approached as a long day hike, though access to higher elevations depends on current activity. The volcano’s size is experienced through wide-ranging approaches and extended travel across loose ash, lava fields, and unstable ground. While altitude is modest, the terrain is physically taxing and unpredictable. For climbers, Etna’s scale is felt in distance, variability, and exposure to active volcanic processes rather than vertical relief.

9. Mount Shasta

Mount Shasta is the largest volcano in the Cascade Range by volume. Its size comes from a complex structure made up of multiple overlapping cones that formed during different eruptive periods. Rather than growing as a single symmetrical peak, Shasta accumulated mass in stages, with each cone adding material without removing earlier deposits.

Mount Shasta is classified as dormant, though it remains capable of future eruptions. Its broad base spreads across a wide area of northern California, giving it far more mass than nearby Cascade volcanoes. Erosion has softened some features, but the mountain retains enormous structural volume relative to its height.

From a climbing perspective, Mount Shasta is typically a two-day alpine ascent, though strong parties sometimes attempt it in a single long push. Most routes involve snow and ice travel for much of the year but are not highly technical. The volcano’s size is felt through sustained elevation gain, long summit days, and exposure to rapidly changing weather. Climbers experience Shasta as physically demanding because of its bulk and vertical relief, not because of technical difficulty.

10. Mount Rainier

Mount Rainier is one of the most massive stratovolcanoes in the United States by total volume. Its size comes from a broad volcanic base built by repeated eruptions, combined with thick glacial cover that adds weight and complexity to the mountain’s structure. Although not among the tallest volcanoes, its footprint and mass dominate the surrounding Cascade Range.

Mount Rainier is classified as active. Its volcanic system remains capable of future eruptions, and large volumes of ice and loose volcanic debris amplify its hazard profile. Much of the mountain’s bulk is hidden beneath glaciers, which conceal the underlying volcanic terrain.

From a climbing perspective, Rainier is a multi-day, glaciated climb. Routes require technical glacier travel, crevasse navigation, and careful weather management. The mountain’s size is felt through long approaches, sustained elevation gain, and extended summit days. Climbers experience Rainier as physically demanding not because of steepness alone, but because its mass forces long hours at altitude while managing objective hazards.

11. Mount Sidley

Mount Sidley is the largest volcano in Antarctica by volume and footprint. It is a shield volcano built by low-viscosity lava flows that spread outward over a wide area. Much of its structure lies beneath ice, but geophysical surveys confirm its substantial underlying mass.

Mount Sidley is classified as dormant. There is no evidence of recent eruptive activity, yet its volcanic origin is clear. Its size reflects slow, sustained eruptions over long geological time rather than explosive growth.

Climbing Mount Sidley is an expedition-level undertaking. The terrain itself is non-technical, but the volcano’s size contributes to long summit days and significant exposure. Access requires complex logistics, extreme cold tolerance, and complete self-sufficiency. For climbers, Sidley’s size is secondary to its remoteness, but the two combine to create a demanding and unforgiving objective.

12. Mount Teide

Mount Teide is the largest volcano in the Atlantic region by total structure. It rises from the ocean floor and forms the central mass of Tenerife. When the submarine portion is included, Teide’s size far exceeds what its summit elevation alone suggests.

Mount Teide is classified as dormant, though the volcanic system beneath it remains active. Its size reflects repeated eruptive cycles that rebuilt the mountain after major collapses, filling calderas and expanding its footprint.

From a climbing standpoint, Teide is typically ascended as a long day hike. The terrain is non-technical but dominated by loose volcanic scree and lava flows. The volcano’s size is felt through distance rather than difficulty. Long approaches, gradual elevation gain, and thin air near the summit define the experience more than steep climbing.

13. Mount Fuji

Mount Fuji is one of the largest volcanoes in Japan by overall volume. While its near-perfect cone is famous, much of Fuji’s mass lies in older volcanic layers beneath the modern summit, created by multiple eruptive phases over time.

Mount Fuji is classified as dormant. Its current shape reflects repeated rebuilding after collapses and eruptions, which added material without significantly increasing footprint in recent history.

Climbing Mount Fuji is usually a one or two-day hike during the official season. Routes are non-technical but involve sustained elevation gain on loose volcanic terrain. The volcano’s size is experienced through long ascents, fatigue from constant upward movement, and exposure to weather rather than technical difficulty. Crowds can also magnify the physical demands of summit day.

14. Sangay

Sangay is one of the largest active volcanoes in Ecuador by volume. It is part of a long volcanic chain and has grown rapidly due to frequent eruptions that continue to add material to its flanks. Unlike dormant giants, Sangay is still actively building mass.

Sangay is classified as active and is among the most persistently erupting volcanoes in South America. Continuous lava output and ash deposition contribute directly to its size and evolving footprint.

Climbing Sangay is rare and highly committing. The volcano’s size creates long, exhausting days, while its activity introduces serious objective hazards. Approaches are multi-day and remote, and unstable volcanic terrain is common. For climbers, Sangay represents the intersection of scale and risk rather than a conventional summit objective.

15. Cotopaxi

Cotopaxi is one of the largest stratovolcanoes in the Andes by total volume. It rises from a high plateau, which amplifies its overall structure and contributes to its prominence across central Ecuador. Extensive lava and ash deposits spread far beyond the visible cone.

Cotopaxi is classified as active. Its size reflects long eruptive cycles combined with repeated glaciation, which reshaped but did not significantly reduce its mass.

From a climbing perspective, Cotopaxi is typically ascended over two days. Routes involve snow and glacier travel, though technical difficulty is moderate. The volcano’s size is felt through long summit pushes, altitude exposure, and the cumulative fatigue of climbing a large, glaciated mountain rather than through steep or complex terrain.

Seven Volcanic Summits

In mountaineering, the Seven Summits are the highest mountains on each continent. They are commonly used as a long-term climbing goal because they span different climates, altitudes, and technical demands. Completing them requires years of experience, careful planning, and significant commitment. For many climbers, the list provides structure and progression rather than a single defining ascent.

A related but lesser-known objective is the Seven Volcanic Summits. This list includes the highest volcano on each continent. Many climbers pursue it after, or alongside, the traditional Seven Summits. The appeal is similar, global scope and clear criteria, but the climbing experience is different.

The Seven Volcanic Summits are:

- Africa: Mount Kilimanjaro

- South America: Ojos del Salado

- North America: Pico de Orizaba

- Europe: Mount Elbrus

- Asia: Mount Damavand

- Antarctica: Mount Sidley

- Oceania: Mount Giluwe

Climbing volcanoes differs from climbing non-volcanic mountains in subtle but important ways. Volcanoes are usually wider, with longer approaches and more gradual slopes. The challenge is rarely technical climbing. It is distance, altitude, loose footing, exposure, and time on feet. Volcanic terrain can be unstable, and active or dormant status can affect access and risk. Climbers who understand these differences plan differently, pace more conservatively, and respect scale over steepness.

This makes volcanic summits a natural extension of high-altitude trekking and endurance-focused mountaineering rather than technical alpinism.