The blue whale is the largest animal on Earth. It’s also the biggest creature to have ever lived. This includes every dinosaur species that has ever existed.

Adult blue whales typically reach 80 to 100 feet (24 to 30 meters) in length and weigh between 200,000 and 330,000 pounds (90,700 to 149,700 kilograms). The largest verified individuals likely exceeded these figures. No land animal, living or extinct, approaches this scale in total mass.

To put that in perspective, the largest known dinosaurs, such as Argentinosaurus, may have rivaled blue whales in length but fell far short in weight. The blue whale holds the uncontested record for sheer biological size.

Even at birth, blue whales are enormous. A newborn calf measures roughly 23 feet (7 meters) long and weighs about 5,000 to 6,000 pounds (2,270 to 2,720 kilograms). That is heavier than a fully grown rhinoceros on day one.

Blue Whale Size Comparisons

- A single blue whale weighs more than 2,000 average adults combined. A human could stand upright inside a blue whale’s heart chamber. A child could crawl through its major arteries.

- A full-grown blue whale is longer than three standard school buses parked end to end. It is roughly the length of a Boeing 737 aircraft from nose to tail.

- In terms of weight, a blue whale equals 25 to 30 African elephants.

- The heart alone weighs about 400 pounds (180 kilograms) and pumps about 60 gallons (227 liters) of blood with each beat at the surface.

- The tongue can weigh as much as 6,000 pounds (2,720 kilograms), comparable to a mid-size SUV.

- The lungs can hold more than 1,300 gallons (4,900 liters) of air. During deep dives, the heart rate can slow to just two to eight beats per minute to conserve oxygen.

- A blue whale’s tail fluke can reach 25 feet (7.6 meters) across. That is wider than a two-lane road. Each fluke weighs roughly as much as a compact car, yet moves with precise control underwater.

How Much Does a Blue Whale Eat?

Despite its enormous size, the blue whale feeds almost entirely on krill. These shrimp-like crustaceans are only a few inches long. During peak feeding season, a blue whale can consume up to 8,000 pounds (3,600 kilograms) of krill per day. This intake is not spread evenly throughout the year. Blue whales feed intensively during summer months in cold, nutrient-rich waters, then rely on stored fat during migration and breeding seasons.

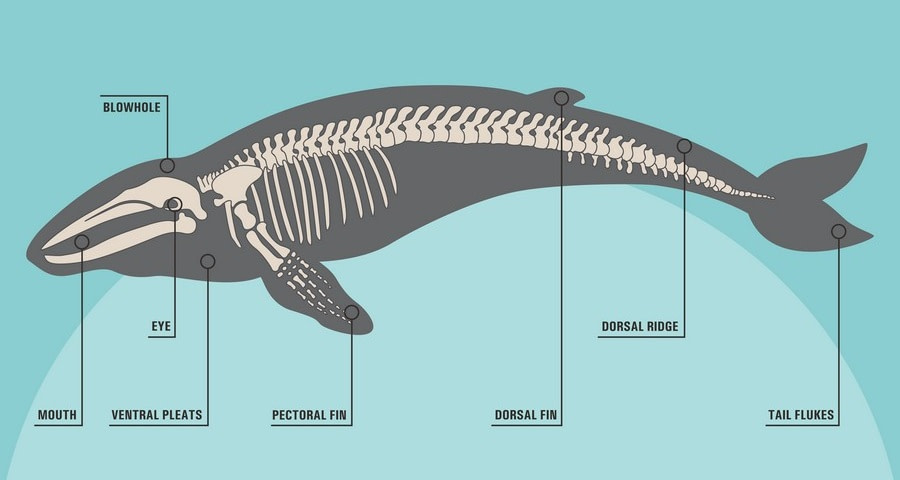

Blue whales are able to eat so much because of its baleen filtering system. Instead of teeth, they have hundreds of baleen plates made of keratin, the same material found in human fingernails. These plates hang from the upper jaw and fray into stiff bristles along the inner edge.

When feeding, a blue whale lunges forward with its mouth open and takes in an enormous volume of water. Specialized throat pleats along the lower jaw expand dramatically, allowing the mouth to hold more than 100 tons (90 metric tons) of water in a single gulp. The whale then closes its mouth and pushes the water out using its tongue. Water escapes through the baleen while krill remain trapped inside.

The whale repeats this process many times during feeding bouts. Daily intake is built gradually through repeated lunges in dense krill swarms rather than a few large mouthfuls.

Baleen and body size evolved together. As whales grew larger, they could take in more water with each lunge. Larger gulps captured more krill. Over millions of years, this relationship allowed blue whales to reach sizes no other animal has ever achieved.

What Makes Blue Whale Anatomy Special

A blue whale’s body is shaped to manage extreme size, not speed or agility. Its long, tapered form reduces drag and allows it to move efficiently through water despite enormous mass.

The ocean itself is a critical part of the design. Water buoyancy supports the whale’s weight, removing the skeletal limits that constrain land animals. On land, an animal of this size would collapse under its own mass. In water, that mass becomes manageable.

The throat pleats used for feeding also play a structural role. When not feeding, they remain folded and streamlined. When feeding, they expand to accommodate massive volumes of water without damaging tissue or restricting movement.

Blubber is another key adaptation. Blue whales carry a thick layer of fat, often 10 to 12 inches (25 to 30 centimeters) thick. This provides insulation in cold oceans and serves as an energy reserve during long migrations and periods without feeding.

Their bones are large but relatively light for their size. They provide strength without excessive density, helping the whale maintain buoyancy and structural integrity.

Limits of Extreme Size

Size solves many problems, but it creates others. Blue whales are not maneuverable. Tight turns and rapid acceleration are difficult. Precision movement is limited compared to smaller whales. Their bodies only function in water. Out of the ocean, their organs and skeleton cannot support their own weight.

Calves remain vulnerable. Young blue whales can be targeted by orcas before they reach full size. Adult whales rely almost entirely on mass as a deterrent rather than speed or aggression.

Blue whales are also tightly linked to krill availability. Changes in ocean temperature, ice patterns, or food chains directly affect their survival.

The Future of the Blue Whale

Blue whales are classified as endangered.

During the early 20th century, industrial whaling pushed blue whales to the edge of extinction. Their size made them valuable targets. A single whale could yield massive amounts of oil and meat. By the time commercial whaling was banned, some populations had been reduced by more than 90%.

Blue whales are no longer legally hunted. International protections now prohibit their capture. However, recovery has been slow. Blue whales reproduce at a low rate, with females giving birth only once every two to three years. Their global population is estimated at roughly 10,000 to 25,000 individuals, a fraction of their historical numbers.

Modern threats are indirect. Ship strikes are a leading cause of death, especially in busy shipping lanes. Noise pollution interferes with communication and navigation. Climate change threatens krill populations by altering ocean temperature and ice patterns. Entanglement in fishing gear is another risk. While adult blue whales have few natural predators, human activity remains the greatest danger to the species.

Its continued survival depends not on size, but on the stability of the oceans it relies on.