Mountaineering’s legitimacy as a “sport” is often questioned.

Unlike conventional sports, which are played in controlled areas, mountaineering takes place in the wilderness, where storms, avalanches, and rockfall occur. To some, the battle between humans and untamed environments represents courage, strength, and endurance. But to many, it looks selfish, irresponsible, and pointless.

When a climber dies on a mountain, the headlines and comments are often harsh.

- “Play stupid games, win stupid prizes.”

- “Such a ridiculous hobby.”

- “I’ll never understand why people climb mountains.”

This article examines how the American public views mountaineers, the perception in other countries, and how mountaineering compares to other dangerous sports.

How Mountaineering is Seen in the United States

In the United States, mountaineering is a niche activity. Mainstream media tends to cover mountaineering only in the wake of tragedy. When deaths occur, the public reaction is often criticism. The victims are labeled as ego-driven or selfish.

In the most positive light, mountaineers are seen as physically fit and mentally tough, with the ability to manage stress and fear. Climbing is framed as a test of endurance and willpower. In this narrative, mountaineers embody the human spirit of adventure. They’re modern day explorers, navigating the most inhospitable places on earth. And those who succeed are praised for overcoming extreme hardship to accomplish a goal.

Celebrities such as Conrad Anker and Jimmy Chin fall into this category.

On the other side, mountaineers are viewed as reckless. To many, climbing high peaks is no different than base jumping or free soloing. That is, participants gambling with death for the purpose of satisfying their egos or for the rush of adrenaline (more on this later). Mountaineers are also seen as selfish, due to the high cost of failure. When climbers die, they leave grieving families. And rescues put others at risk. So to critics, the act of climbing is not just dangerous to the mountaineer but unfairly impacts others.

In 1996, the Everest disaster that killed eight climbers made global headlines. American coverage framed it as hubris: rich and unprepared amateurs who over relied on their guides and Sherpa, but were in over their heads. More recently, the viral photos of long lines on Everest’s reinforced the view that climbing big mountains is an ego-driven pursuit.

However, the perception of mountaineering is not universal. It differs from region to region.

How Mountaineering is Seen Elsewhere

Modern alpinism was born in the Alps. Peaks like Mont Blanc, the Matterhorn, and the Eiger are cultural landmarks as much as they are climbing objectives. In Europe, mountaineering is viewed as an athletic undertaking, not a reckless hobby.

Mountaineers are seen as real athletes. In mountain towns like Chamonix and Zermatt, climbers are honored. Names like Sir Edmund Hillary, Reinhold Messner, and Ueli Steck are widely recognized. Ascents are reported like sports results. Guiding is treated as a serious profession and a viable, long term career. Risk is accepted but managed, and climbers are expected to be skilled and competent.

There is also a pragmatic view. For those who grow up near the mountains, alpinism is part of everyday life. Local economies value the activity. This support shapes public opinion. Familiarity makes climbing feel credible and structured, not fringe. Criticism still exists, but it is aimed at poor decisions rather than the sport itself. Deaths do not bring accusations of selfishness; they are accepted and understood as the price of alpinism.

In the Himalayas, climbing is tied to spirituality and national pride. The highest peaks are considered sacred and guiding is regarded as a skilled profession that sustains entire communities. Governments in the region actively promote mountaineering. Nepalese climbers, such as Nims Purja, are recognized as elite athletes. Debate rarely focuses on whether people should climb at all, but rather on issues of overcrowding, exploitation, and environmental impact.

Similarly, in the Andes, mountaineering is woven into cultural identity. In countries like Peru, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina, climbers are viewed with respect. Andean people have lived at altitude for generations, and they know what it takes to conquer big peaks.

Mountaineering Deaths Compared to Other Sports

Mountaineering is often disparaged for its dangers, yet when compared to other sports the risks are not out of line. Mountaineering accounts for 4–6 deaths per 100,000 participants annually in the United States. Other sports show similar or even higher injury and fatality rates.

- Hiking: ~0.1–0.3 deaths per 100,000 hikers annually in the U.S., usually from falls, medical events, and environmental exposure.

- Outdoor Rock Climbing: ~0.5–0.7 deaths per 100,000 climbers. Injury rates are much higher, but fatalities are rare compared to high-altitude mountaineering.

- Running/Marathons: ~0.5–1 deaths per 100,000 participants per year. Most fatalities are cardiac-related, often during marathons.

- American football: 0.5-1 deaths per 100,00 players in the United States. Concussions are routine, and long-term brain injury is common.

- Skydiving: 1 death per 100,000 licensed skydivers. There are about 20 deaths per year among ~350,000 U.S. licensed skydivers.

- Boxing: 1-2 deaths per 100,000 active U.S. fighters per year. Global data shows far higher fatality rates – closer to 13 per 100,000 fighters.

- Road cycling: 2-3 deaths per 100,000 participants annually in the U.S. Risk is highest on roads due to traffic. Much higher for serious road cyclists logging many miles.

- Big mountain skiing: 3-4 per 100,000 skiers. Most fatalities are caused by avalanche.

- Horseback riding: 7-10 deaths per 100,000 riders, with around 37 injuries per 100,000 hours of riding and more traumatic brain injuries than football.

- Scuba diving: 17 deaths per 100,000 divers. That translates to 70–100 U.S. fatalities annually, most linked to drowning, embolism, or poor gas management.

- Rodeo riding: ~20 deaths per 100,000 rodeo riders. Head and neck trauma is the most common cause.

Interestingly, these sports are typically not condemned as selfish or reckless. Football and boxing are considered legitimate competitions. Cycling and running are viewed as healthy, mainstream recreational activities. Big mountain skiing is not admonished, but admired for its high risk, athletic brilliance. Scuba is marketed as leisure tourism – a way to view wildlife and reefs. And horseback riding and rodeo are upheld by long-standing American traditions.

Mountaineering is judged differently, even though the fatality rates are comparable to sports that society not only accepts, but celebrates. Given the probability of death, mountaineering is not uniquely dangerous. In the United States, the fatality rate in mountaineering is higher than football and running, somewhat higher than bicycling and cycling, comparable to big mountain skiing, and lower than horseback riding or scuba diving. If death rates alone define recklessness, then these sports should be judged the same way. But, the mountaineer is unfairly singled out among boxers, cyclists, skiers, horseback riders and scuba divers.

When evaluated using the same standards as other sports, mountaineering is not more reckless.

Should Mountaineers Be Rescued?

Needing help in the mountains is unlike other sports.

On a football field, medics are standing by. In a marathon, ambulances line the course. In mountaineering, rescues are often large scale operations that pose deadly threats to the rescuers. This creates an ethical dilemma. Should others risk their lives to save someone in distress?

Mountaineers are said to be selfish because they rely on rescuers to save them when they get in trouble. But this assumption overlooks the mindset of most climbers. That is, they don’t expect to be rescued. Self-sufficiency is engrained as part of the challenge.

On many high mountains, rescue is impossible above certain altitudes. On the slopes of Mount Everest, more than 200 bodies of those who died climbing it still remain on the mountain. Due to the risk, cost, and effort involved, recovery of the bodies, is impractical or unjustified. That’s a sad, but undeniable truth. Foul weather often prevents movement in and out of danger zones for both rescuers and their subjects. Climbers understand this reality.

As for putting others in danger, it’s worth noting who the rescuers are. Search and rescue teams are made up of mountaineers themselves. They know the risks and choose to accept them, just like the climbers they try to help. Their actions are voluntary. This separates mountaineering from activities where rescuers are obligated to respond.

Rescue in the mountains is therefore not a safety net. It is an uncertain possibility. To label climbers selfish for requiring it misunderstands the ethic of the sport. Unlike other athletes, mountaineers step into an environment where the default assumption is that no one is coming. Survival is your own responsibility.

The Adrenaline Misconception

One of the most persistent misconceptions is that mountaineers are chasing an adrenaline rush. This is just plain wrong.

Mountaineering is slow, methodical, and often monotonous. It’s low grade suffering for long periods of time. Climbers spend hours traveling from one camp to another, while carrying heavy loads and rationing their energy. Adrenaline rushes are detrimental, and usually a sign that something has gone wrong. Physiologically, adrenaline spikes the heart rate and burns energy rapidly. For optimal endurance, climbers want to stay calm and level headed, not excited.

Mountaineers are not thrill-seekers.

Is Climbing Kilimanjaro Mountaineering?

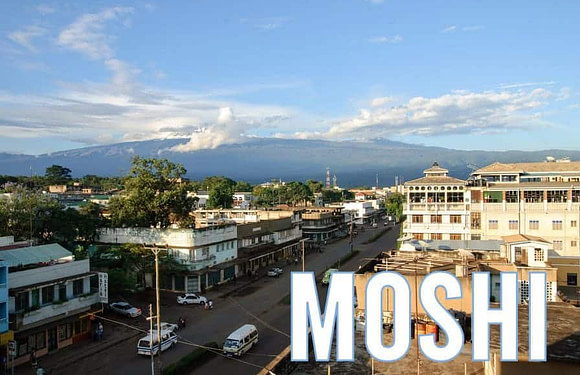

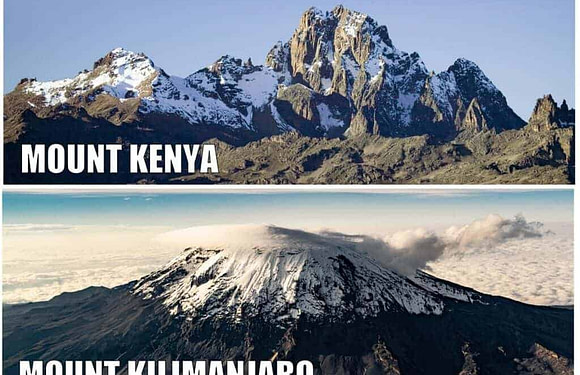

Kilimanjaro often gets lumped in with high-altitude mountaineering, but it is very different from the world’s technical peaks. At 19,341 ft (5,895 m), it is the tallest mountain in Africa, but the route to the top is a hike, not a technical climb. No rock or ice climbing is required and the threat of falling, rockfall or avalanche is minimal.

For this reason, Kilimanjaro is considered a high-altitude hike. Thousands of people attempt it each year, most with no prior climbing experience. With proper acclimatization and support, the success rate is high and the risks are relatively low. Deaths do occur, but almost always from altitude sickness or preexisting medical conditions, not from accidents on the mountain.

Kilimanjaro is therefore seen less as an extreme sport and more as an adventure travel experience. It introduces people to high altitude without exposing them to the hazards of technical climbing. For many, it is the first step into the mountains.

Conclusion

Are mountaineers selfish and reckless?

The reality lies in perspective. Statistically, mountaineering is no more deadly than other mainstream sports. Yet outside of mountaineering, participants are rarely condemned. The difference is cultural. When athletes step into arenas, fields, or rings, the risk is normalized. But in the mountains, the risk is criticized. Summiting a peak may very well be an unnecessary risk. But so is getting punched in the head, riding a bike at high speeds, or exploring underwater wrecks.

If mountaineering is to be judged, it should be judged by the same standards as other sports. In this regard, it is objectively not more reckless, nor more selfish. It is simply another way human beings choose to measure themselves. You might say that is ego. But the same could be said of every athlete who tests their limits, no matter where it occurs.

Today, mountaineering sits between admiration and condemnation. Whether it is viewed as selfish or heroic depends less on the climber and more on the culture that judges him.