Endurance is not about speed. It is the ability to sustain effort over distance and duration. Whether migrating across continents, hunting for hours, or traveling for weeks without rest, in the animal world, endurance determines survival. Some species excel because of biology. Others, through adaptation.

| Recommended Routes | 1 person | 2 person | 3 person | 4 person | 5 person | 6 person | 7 person | 8 person | 9 person | 10+ persons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 day Northern Circuit☀️ | $6,119 | $4,849 | $4,269 | $3,969 | $3,939 | $3,859 | $3,789 | $3,759 | $3,719 | $3,669 |

| 9 day Northern Circuit | $5,859 | $4,599 | $3,999 | $3,689 | $3,659 | $3,589 | $3,509 | $3,489 | $3,449 | $3,389 |

| 9 day Northern Circuit☀️ | $5,859 | $4,599 | $3,999 | $3,689 | $3,659 | $3,589 | $3,509 | $3,489 | $3,449 | $3,389 |

| 8 day Northern Circuit | $5,199 | $4,149 | $3,639 | $3,349 | $3,339 | $3,269 | $3,209 | $3,169 | $3,129 | $3,089 |

| 9 day Lemosho Route☀️ | $5,779 | $4,519 | $3,959 | $3,669 | $3,639 | $3,569 | $3,489 | $3,469 | $3,419 | $3,369 |

| 8 day Lemosho Route | $5,149 | $4,099 | $3,599 | $3,349 | $3,319 | $3,249 | $3,199 | $3,149 | $3,119 | $3,099 |

| 8 day Rongai Route☀️ | $5,049 | $4,049 | $3,589 | $3,339 | $3,289 | $3,239 | $3,199 | $3,149 | $3,109 | $3,079 |

| 7 day Rongai Route | $4,649 | $3,719 | $3,259 | $3,019 | $2,999 | $2,949 | $2,889 | $2,849 | $2,819 | $2,769 |

| 8 day Machame Route☀️ | $4,989 | $3,969 | $3,549 | $3,309 | $3,289 | $3,189 | $3,159 | $3,099 | $3,069 | $3,059 |

| 7 day Machame Route | $4,539 | $3,649 | $3,209 | $2,989 | $2,969 | $2,899 | $2,849 | $2,819 | $2,789 | $2,779 |

Note on VO₂ Max

VO₂ max measures how much oxygen an animal (or human) can use per kilogram of body weight per minute. It reflects aerobic capacity. The higher the number, the more efficiently oxygen is delivered to muscles during sustained effort. Endurance athletes, both human and animal, consistently show high VO₂ max values, allowing them to maintain activity for long periods without fatigue.

10 Animals With the Best Endurance

1. Human

Humans are the greatest endurance athletes on Earth. Our species evolved to travel extreme distances over long periods. Ancient hunters once chased antelope until the animals collapsed from exhaustion under the sun. Today, elite ultramarathoners can cover more than 100 miles (160 km) in 24 hours.

The secret lies in heat control and energy efficiency. Humans shed heat through millions of sweat glands, while most animals must stop to pant. Long legs, springy tendons, and short toes reduce energy cost per stride. Our large gluteus maximus stabilizes the torso for hours of running. The ability to switch between burning carbohydrates and fat extends endurance far beyond glycogen limits.

Mentally, humans are unique. We endure pain and fatigue through willpower, not instinct. Endurance running shaped our evolution, separating us from all other primates.

2. Sled Dog (Alaskan Husky)

Sled dogs define cold-weather endurance. During races like the Iditarod, teams run over 100 miles (160 km) per day for more than a week. Each dog maintains near-constant aerobic output while pulling weight across ice and snow.

Their muscles rely primarily on fat oxidation, conserving glycogen for recovery. This metabolic flexibility gives them unmatched staying power. Their VO₂ max surpasses 200 ml/kg/min – roughly triple that of elite human runners. Thick fur insulates against windchill while specialized paws dissipate heat. Even in extreme cold, they regulate body temperature efficiently through rapid breathing.

Selective breeding refined their endurance, mental drive, and recovery speed. Despite exhaustion, dogs often wag their tails between runs, signaling readiness for more. No other animal performs so intensely for so many consecutive days.

3. Horse

The horse has been humanity’s endurance partner for thousands of years. Arabian horses routinely cover 100 miles (160 km) in a day during endurance races. Their efficiency lies in powerful lungs, a large heart, and springy leg tendons that store and release energy.

Horses maintain a steady 8 mph (13 km/h) trot for hours with minimal fatigue. They sweat heavily, using evaporation to regulate temperature during exertion. Muscle fibers are highly oxidative, allowing sustained aerobic work. Their VO₂ max rivals that of elite sled dogs.

Selective breeding amplified traits for stamina, heart size, and recovery. Horses thrive on rhythm and pacing – the essence of endurance. Their power, grace, and reliability have made them the backbone of long-distance travel throughout human history.

4. Reindeer (Caribou)

Reindeer are among the strongest endurance animals on land. Their annual migration can reach 3,000 miles (4,800 km), one of the longest of any mammal. They travel 20 to 40 miles (32 to 64 km) a day across tundra, snow, and uneven ground.

Reindeer rely heavily on slow-twitch muscle fibers that favor aerobic efficiency. Their hooves widen in winter to create natural snowshoes, reducing energy loss over soft surfaces. Seasonal shifts in metabolism allow efficient switching between fat and carbohydrate, allowing long-distance movement with limited food. They can maintain steady pace in freezing winds and harsh temperatures, protecting vital organs with dense fur and excellent insulation. Specialized nasal passages warm cold air before it enters the lungs, reducing thermal stress during long travel days.

Herd structure also improves efficiency, as movement in groups reduces wind resistance. Endurance for reindeer is a survival strategy, practiced over thousands of miles every year.

5. Camel

The camel reigns supreme in endurance across deserts. It can walk 25 miles (40 km) per day for ten straight days without water.

Its secret lies in water conservation. Camels lose up to 30% of their body weight through dehydration and survive – something fatal to nearly every other mammal. Their red blood cells are oval, maintaining flow when water is scarce. Body temperature swings widely between day and night, reducing the need to sweat. Fat stored in the hump converts to both energy and metabolic water.

When rehydrating, a camel can drink 30 gallons (135 liters) in minutes without harm. Long legs and padded feet handle shifting sand with ease. Endurance for camels means surviving what others cannot. They are the desert’s long-haul champions.

6. African Wild Dog

The African wild dog is a relentless hunter of the savanna. It chases prey for up to 30 minutes at speeds near 35 mph (56 km/h), rarely giving up. Success rates exceed 70%, far higher than lions or cheetahs.

Their light frames, large lungs, and efficient gait make long-distance pursuit possible. Teamwork is key. Dogs rotate the lead position to share the effort. Oversized ears act as radiators, shedding excess heat during the chase.

Their endurance hunting strategy depends on constant movement and cooperation. While other predators sprint, wild dogs outlast. They are endurance specialists built for coordination, heat control, and persistence. The sight of a pack running in formation is nature’s version of a marathon in motion.

7. Wildebeest

Wildebeest represent endurance on a continental scale. Every year, millions migrate up to 1,000 miles (1,600 km) through the Serengeti and Maasai Mara.

Their steady, energy-efficient gait allows them to travel day after day. Broad shoulders and muscular legs keep them moving across plains and rivers. They can trot for hours at 10 mph (16 km/h) without tiring. Efficient digestion allows them to subsist on dry grass, and their bodies conserve water well. Calves stand and run within minutes of birth, joining the migration almost immediately.

Herd movement provides aerodynamic and energetic advantages. This cycle of endurance migration sustains one of the planet’s largest ecosystems.

8. Wolf

Wolves are endurance hunters of the north. A pack can cover 40 miles (64 km) in a single day while tracking prey. They trot at 6 mph (10 km/h) for hours, saving energy for short sprints when attacking.

Their lean bodies, long legs, and strong cardiovascular systems support aerobic efficiency. Wolves often follow herds for days, wearing prey down through persistence. Cold climates demand constant motion, keeping packs lean and muscular. Cooperation within the pack conserves energy, as members share hunting and tracking duties. Wolves rarely rest long, always moving toward food.

9. Yak

The yak is a high-altitude endurance specialist. It spends most of its life above 13,000 feet (4,000 m), where oxygen levels are too low for most mammals.

Yaks carry heavy loads for hours at a steady pace without fatigue. Their lungs and heart are proportionally larger than those of lowland cattle. Blood is rich in hemoglobin, allowing efficient oxygen delivery in thin air. Thick fur traps heat and protects against wind, letting them move comfortably in cold conditions.

The metabolism favors slow, steady aerobic output instead of short bursts of power. Even with sparse vegetation, yaks maintain enough energy for demanding travel days. The species survives by moving efficiently, conserving heat, and optimizing oxygen use at altitude.

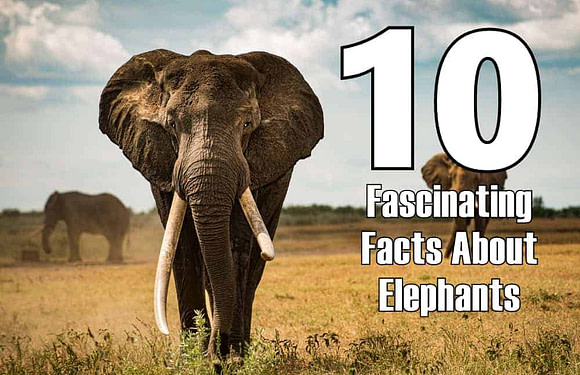

10. African Elephant

The African elephant’s endurance lies in scale and memory. Herds can travel 50 miles (80 km) per day, guided by knowledge of distant water sources. Their massive hearts, weighing 40 pounds (18 kg), pump efficiently through enormous bodies.

Elephants conserve energy by walking slowly but steadily. Padded feet reduce impact, and long legs make each stride efficient. Their endurance extends over months as they migrate across vast landscapes. Matriarchs recall routes passed down through generations, leading herds to survival. Elephants endure not just through strength but through intelligence and patience.

Endurance Beyond Land

In water and air, endurance operates under different physics. Land animals rely on muscle power, energy reserves, and thermal regulation for efficient movement. Marine and aerial species, by contrast, use physics (lift, glide, and buoyancy) to go farther.

Endurance in water is built on streamlining, oxygen storage, and insulation. The leatherback turtle and humpback whale are among the most enduring marine travelers. Leatherbacks cross entire oceans on little food, using a smooth, tapered body to minimize drag. Humpbacks migrate 5,000 miles (8,000 km) each year, gliding between tail strokes to conserve energy. Both store oxygen in muscle-bound myoglobin and slow their heart rates to extend dives. Thick blubber provides warmth and a steady energy reserve.

In the air, the champions are birds like the Arctic tern and the albatross. The Arctic tern holds the record for distance, flying up to 44,000 miles (71,000 km) annually between the poles. Albatrosses use wind currents and dynamic soaring to circle the Southern Ocean for months with little exertion. Hollow bones reduce weight, while large wings produce lift efficiently. Oxygen-rich blood and powerful flight muscles sustain long periods of motion.